When HBO Max announced that it would temporarily remove Gone With the Wind from its platform, in order to place a statement in front of it putting the film’s content into the proper context, it set off a firestorm of controversy online and in the media. Some decry the decision as censorship. Others believe that the movie speaks for itself and doesn’t need context. Still others lauded the decision, asserting that any and all attempts to educate viewers should be encouraged. Today, The Washington Post reported that the film would be back on the platform this week, with an African-American Studies scholar speaking at the front of it.

Controversy is not new to Gone With the Wind–it came under scrutiny for its depictions of slavery and race even before the film was released. Black-led organizations warned producer David O. Selznick, as early as pre-production, that he should tread carefully with his adaptation of Margaret Mitchell’s novel. It included offensive language and stereotypical depictions that would not be tolerated by the Black moviegoing public. Indeed, Selznick listened to the warnings about language (due in part to fears of protest that would certainly carry over from a planned re-release of Birth of a Nation the same year), but was walking a thin tightrope between the need for honest depictions of Black people and the financial need for the film to play in the merciless Jim Crow South. When the film was finally released, it received a storm of controversy from the Black press. Many Black critics praised Hattie McDaniel’s layered and nuanced performance as Mammy, and (somewhat surprisingly by today’s standards) praised the film’s restraint. The Crisis, the quarterly journal of the NAACP, wrote that Gone With the Wind “eliminated practically all the offensive scenes and dialogue” from the original book.

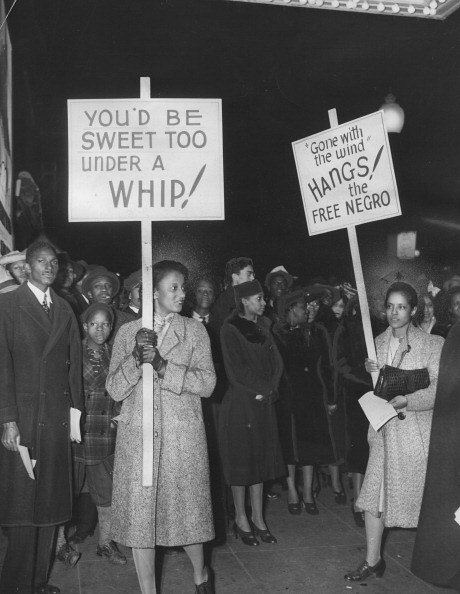

But Carlton Moss, writing for The Daily Worker, disagreed. The film was “sugar-smeared and blurred by a boresome Hollywood love story,” he stated, and he condemned Mammy’s devotion to the O’Haras, who “helped to keep her people enchained for centuries.” Black activists picketed and actively protested the film across the United States, with shouts of “Negroes were never docile slaves!” and “Gone With the Wind glorifies slavery!” Picketers carried signs outside theaters that were designed to elicit intense responses from the public.

A protest of Gone With the Wind in Washington, D.C.

As the film has aged, and became the cultural phenomenon that it is, the scrutiny and controversy continues. Theaters have cancelled showings of the film after public outcries of protest, followed by accusations of censorship for the cancellations. This latest controversy due to the move by HBO Max is only a continuation of the trend, not something new.

In this era where entertainment is literally at our fingertips, and access to Gone With the Wind is as easy as a push of a few buttons, I feel that it is dangerous and irresponsible to allow such an inherently controversial film to be viewed in such a way, without proper context. The tradeoff for such rapid-fire consumption of information is that for many people, there is no time for critical thinking, or analysis of the what, why, and how of the material they consume. In the interest of public safety in this era, I fully support HBO Max’s decision to pull Gone With the Wind until proper context can be provided.

I also urge them to add content not just by a scholar of African-American Studies, but a scholar of the African-American experience on film. A few years ago at the TCM Classic Film Festival, I attended a wonderful panel on Gone With the Wind led by Dr. Donald Bogle. Bogle is the pre-eminent historian on Black Hollywood and an instructor at New York University and UPenn. He is an impressive speaker and personally knew many of the biggest figures of African-American classic Hollywood, and his perspective would lend a personal dimension to the film. Also on the Gone With the Wind panel was Dr. Jacqueline Stewart, instructor at University of Chicago and current host of Silent Sunday Nights on TCM. Her knowledge of classic Hollywood in general, as well as her expertise on the African-American experience on film, would also be an excellent addition to HBO Max’s reinstatement of Gone With the Wind.

Donald Bogle and Jacqueline Stewart

I want to close on a positive note regarding Gone With the Wind. Yesterday was the birthday of Hattie McDaniel, “Mammy” in the film, who was an actor, a poet, a songwriter, an intellectual, and activist. She was one of the most prolific supporting players in Hollywood, though her roles rarely deviated from that of a maid. When she was selected for an Academy Award nomination, the Black sorority Sigma Gamma Rho endorsed her and wrote to David O. Selznick: “We trust that discrimination and prejudice will be wiped away in the selection of the winner of this award, for without Miss McDaniel there would be no Gone With the Wind.” McDaniel won, and became the first African-American to receive an Academy Award.

_03.jpg)