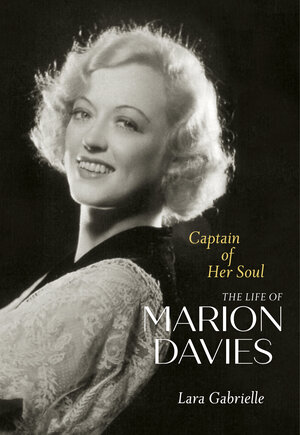

By Lara Gabrielle Fowler

Day 3 started with a bang, as the first event of the day was a very special one. Jane Fonda was scheduled to have her hand and footprints put in the courtyard of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, right alongside those of her father, Henry Fonda. The event was very crowded, and the security tight and closely monitored. For obvious reasons, this is to be expected at an event for a major celebrity, especially one who is as politically controversial as Jane Fonda. Once all attendees successfully passed the security screenings, the event began. We saw a number of major celebrities in attendance, including Jim Carrey, friend and 9 to 5 costar Lily Tomlin, brother Peter Fonda, and longtime friend Maria Shriver. Jane Fonda’s son gave a keynote address, followed by warm words from Lily Tomlin and Maria Shriver. My friends and I happened to be in a spot where we could see Jane behind the scenes as the speeches were read, and she was clearly very emotionally moved. Because of the massive crowd, pictures were hard to get. Here are a few pictures from the official TCM collection of the event.

The ceremony slowly began to break up after Jane’s prints were sufficiently down in the cement, and we began to prepare for the next event–a screening of On Golden Pond (1981) introduced by Jane, clearly the woman of the day. She told some beautiful stories about the filming, particularly relating to her relationship with Katharine Hepburn on set. Jane Fonda was the perfect person to introduce the film, as she had a position as actor and producer on the film as well as being Henry Fonda’s daughter. It was wonderful to hear her talk.

This widescreen print magnified the lush beauty of the photography, shot on location in New Hampshire with breathtaking shots of the fall leaves and loons. It is a simple story, taken from the stage play about Norman and Ethel Thayer (Katharine Hepburn and Henry Fonda), an elderly couple dealing with the effects of age. Norman’s failing health and grumpy personality alienate everyone around him, but Ethel is devoted to him and loves him unconditionally and with all of her soul. Norman and their daughter Chelsea (Jane Fonda) have a severely damaged relationship due to Norman’s inability to be a demonstrative father, and much of the movie deals with their healing process as Norman nears death. It is a beautiful movie on so many levels. The relationship between Norman and Ethel is one that I think everyone hopes they will have with their spouse as they age together, and watching Hepburn and Fonda together is so touching that the mere thought of it provokes tears.

Next up was the brilliant comedy The Lady Eve, another in the Fonda family pantheon. Henry Fonda plays Charles, the heir to a beer fortune who, unbeknownst to him, gets mixed up with a father and daughter pair of card sharps on a cruise ship. He ends up falling in love with the daughter Jean (played by Barbara Stanwyck), and when Charles finds out who she is, he breaks off the relationship. To get him back, Jean collaborates on an elaborate plan to pose as the Lady Eve Sidwich, fictional niece of wealthy Sir Alfred McGlennan Keith. “Lady Eve” and Charles fall in love all over again, and Charles is none the wiser that this is the same woman with whom he had broken up on the cruise ship.

This is a classic screwball comedy by the brilliant Preston Sturges, who has a unique and specific style that leaves its mark on any movie he makes. As film historian Carrie Beauchamp said at the beginning of the screening, Sturges’ films center on dialogue and a hand-picked, stellar cast. The supporting cast in The Lady Eve is especially good, with Sturges mainstay William Demarest, Eugene Pallette, and Charles Coburn playing small but significant roles.

Below is a scene which Roger Ebert called the sexiest scene ever on film. The Hays Code forced filmmakers to be cleverer with their depiction of sexual or steamy content, and this scene is a prime example of how a scene can be extremely charged without the two leads ever even hugging or kissing.

Next on the agenda was Mildred Pierce (1945) with special guest Ann Blyth, Veda in the film. By all accounts that I have heard, Ann Blyth is one of the nicest celebrities in Hollywood, and she certainly showed that tonight. Gentle and sweet, she is the complete polar opposite of her character in Mildred Pierce. Robert Osborne interviewed her about her time in the movies, and she spoke of nothing but good memories of Joan Crawford, a celebrity who often gets a bad rep in Hollywood gossip circles.

Mildred Pierce is another wonderful ensemble movie, though the plot centers around the relationship between Mildred (Joan Crawford) and her devotion to her daughter Veda, who proves to be a spoiled, ungrateful child with an evil streak. The supporting cast includes such character actors as Jack Carson and the witty and hilarious Eve Arden, who pops up and provides some oft-needed comic relief every now and then.

This was the third time that I had seen Mildred Pierce on the big screen, and it never fails to impress me. It is wonderful on the small screen, wonderful on any medium, but there is nothing like the big screen for this movie. Everything is accentuated and magnified, and Veda’s evil is all that more powerful.

For a previous post I have written about the costumes of Mildred Pierce, click here.

Stay tuned tomorrow as Backlots puts the blame on Mame, with a review of Gilda!

_03.jpg)