Hello, dear readers! I usually make it a point to post at least once a week, but due to an inordinately busy schedule over the past few days, that goal has eluded me. But here I am, ready to post about one of the things that has been occupying my time away from the blog.

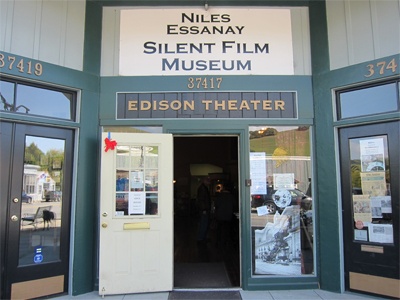

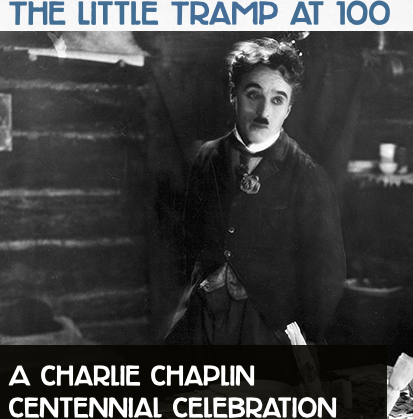

In the quaint Niles district of Fremont, CA lives the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, a little theater with a huge heart. It celebrates an integral part of this town’s heritage–one of which few people are aware. When visitors come to Fremont, little do most people know that it was here that one of the top early film companies, Essanay Studios, flourished and produced a multitude of films in the early 1900s. Charlie Chaplin produced many of his early films here. Broncho Billy Anderson, the first Western star, was born out of Essanay Studios. It was a major focal point for the film industry, and the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum aims to educate the public about its history through tours, films, and festivals.

This weekend will be the Broncho Billy Silent Film Festival, an annual occasion that celebrates not only the legacy of Broncho Billy in Niles, but also the art of silent film as a whole. I have been busy volunteering and preparing for this festival, and I am happy to say that it’s going to be a great one this year. The opening night movie will be The Big Parade, the 1925 King Vidor epic that I consider to be among the top 5 silent films ever made. It will be followed by many other great features and shorts throughout the weekend, including a showing of Charlie Chaplin’s The Circus and the rarely seen 1928 comedy The Spieler, starring Alan Hale and Renee Adoree.

Sunday is the real kicker. Following group of her films, the festival will be graced with its guest of honor, the beautiful and talented 95-year-old Diana Serra Cary–the former Baby Peggy.

Between 1920 and 1924, Baby Peggy-Jean Montgomery was the toast of Hollywood. At the height of her fame, her film grosses equaled those of Charlie Chaplin, and she was one of the top three child stars of the silent era along with Jackie Coogan and Baby Marie. In 1924, her career took the turn of far too many Hollywood child stars–her stardom waned after her money was squandered by her father. She was relegated to vaudeville, and ultimately returned to Hollywood to work in bit parts to pay the bills. Later on, wanting to rid herself of the pain of Baby Peggy, she reinvented herself as Diana Serra Cary–becoming a prominent author, film historian, and activist for children’s rights. It was as Diana Serra Cary that she wrote a biography of former Hollywood rival Jackie Coogan, and that she became active in A Minor Consideration, an organization that advocates for children in the entertainment industry. And at 95 years old, she’s still going.

Now for the big news. I will have the unparalleled honor of interviewing Diana Serra Cary onstage at the Broncho Billy Silent Film Festival on Sunday. If you are in the area, please come out and see Circus Clowns, Peg O’ the Mounted, and the 2013 film Broncho Billy and the Bandit’s Secret in which Diana Serra Cary has an appearance at the age of 94. And see my Q&A with her between films! It promises to be a great day.

Here is the site for ticket information. You can reserve them online, or buy them at the door. I look forward to seeing you there!

_03.jpg)